The atomic and molecular world is abuzz with frenetic motion. Because they are so small and light, molecules and atoms react incredibly quickly to forces that act on them. Chemical reactions, in which molecules join or split, can take place in mere quadrillionths of a second.

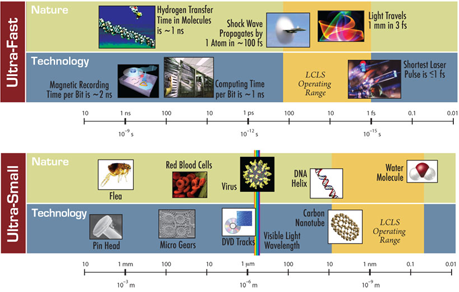

Because all chemistry relies on the extremely rapid motion and arrangement of electrons and atoms, understanding their motions on ultrashort timescales will reveal clues about how chemical processes take place. The LCLS—with its ultrafast hard X-ray pulses of less than 100 femtoseconds (100 femtoseconds = 1/10 of a quadrillionth of a second)—will provide an ideal platform for characterizing these processes as they happen.

The Photon Ultrafast Laser Science and Engineering (PULSE) Institute aims to guide this exciting new field of inquiry.

Since well before the start of LCLS construction, experiments at the PULSE Institute have been gaining momentum. In one recent experiment, PULSE researcher Markus Guehr, working together with grad students Brian McFarland and Joe Farrell at a laser laboratory on the Stanford campus, is developing a laser technique called "high harmonic generation." Based on phenomena first observed in 1993 by researchers in France, high harmonic generation is a technique wherein laser light, focused onto cooled atoms or small molecules, causes the atoms each to behave like ultra-miniature accelerators. The result is a spectrum of light emitted by the atoms that is more energetic than the light put into the system, and which can reveal information about how the nuclei and electrons continually rearrange themselves over extremely short timescales.